Al Faḩāḩīl Artist Statement

http://rodneymills.com/weqtweo/how-to-spot-fake-adidas-adilette-comfort.html

In Search of Mohamed is a set of multi-channel videos and photography works, for which I used my first name, Mohamed, as a starting point in research. Growing up in Egypt, there was very little the name provided in way of standing out from the crowd. In a country of 100 million, I was sharing my name, Mohamed, with 14 million people. And so, it was hardly a name that represented individuality; rather, it became a representation of fitting in. Moving to Australia, I started to have different thoughts about the name as it was no longer a mere article that designated me as part of the society.

The name Mohamed refers to the Prophet of Islam. While millions of people share the name, the visual depiction of the Prophet is prohibited, creating tension between reverence and the profane. The project explores this site of ambiguity by creating a manifold portrait of Mohamed appropriated from Egyptian cinema. Films have been collected, viewed, archived, and manipulated to highlight the ghostly boundaries of representation. The selection criteria involved using the name Mohamed in different contexts, and re-presenting the collection in photographic, audio-visual, slide projection, and sculptural forms.

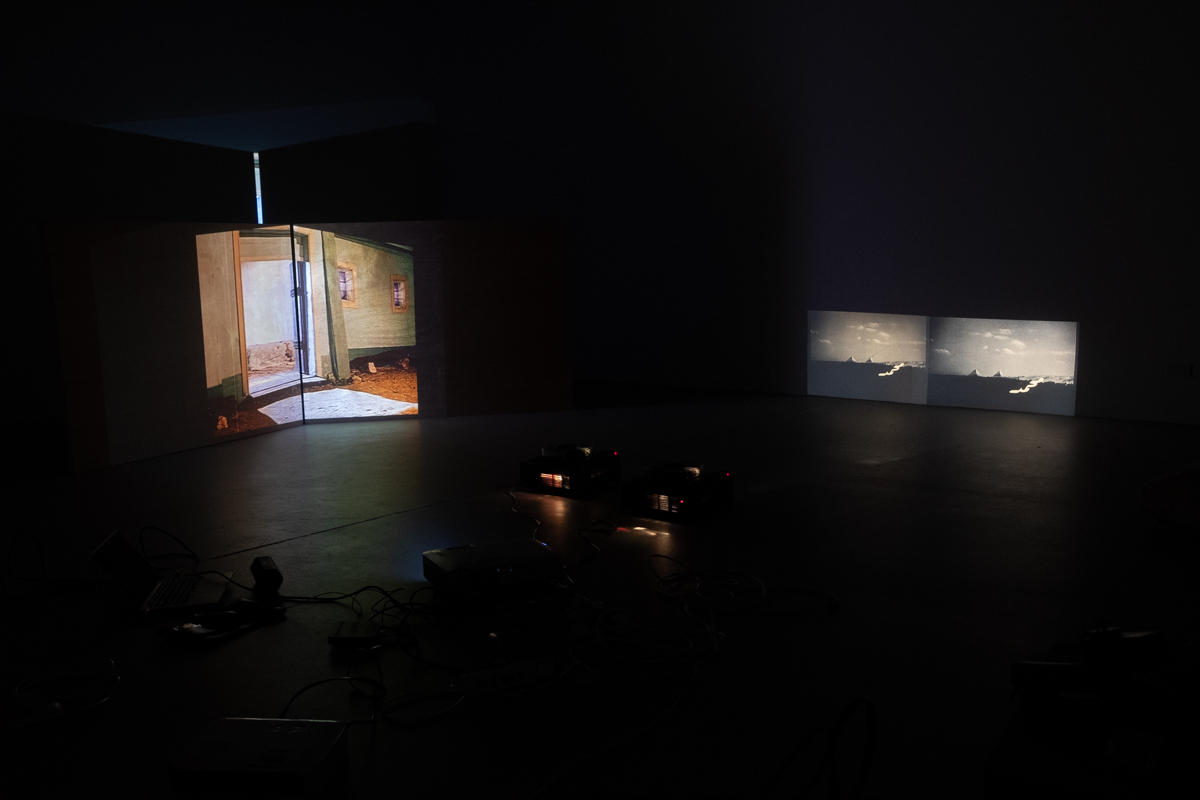

Two video works were created from a collection of excerpts from films about the beginning of Islam and the story of the prophet Muhammad. These films, which were broadcasted on the national television in Egypt during religious holidays, used abstract means to indicate his presence. The first video work, ‘In search of Mohamed: following the invisible’, shows repetitive actions of doors being self-opened and closed while an invisible body, depicted as light, is walking through them. The second part of the video narrates the story of the Israʾ and Miʿraj, a night journey that mentions, according to the Islamic literature, how the prophet Muhammad traveled to Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, then ascended to heaven where he spoke to God. The journey used to be illustrated in miniature paintings when it was accepted to portray the prophet Muhammad with an exposed face. That was between the 14th and the 17th centuries (1). However, from the 18th century onwards, the revealing of the prophet’s portrait started to be banned. And now, it is prohibited to explicitly depict his image in any form. In the films, a halo of light has been incorporated as a symbolic representation of the prophet during that journey.

Additionally, the photographic series ‘In search of Mohamed: abstract portraits’, includes a selection of film-stills taken of those symbolic representations from the same films mentioned above, or recent Middle Eastern films I encountered during my research. Each film-still has been printed then re-photographed using large-format or 35mm cameras, then it was experimentally processed using acids, domestic chemicals and bleaches, sometimes exposed to light leaks that add another layer of abstraction and ambiguity to the representation.

‘In search of Mohamed: relics #2; footprint’ is a bronze sculpture that has been made in response to the video. The sculpture imitates a footprint which is claimed to be the prophet Muhammad’s and is preserved in the Topkapi Museum in Istanbul, which I visited in 2019. Various footprints that were claimed to be the prophet’s were collected from different locations and were often used by sultans ruling in the name of Islam to enhance their popularity and legitimacy (2). The sculpture was made in clay then it was transformed into bronze, similar to the sacred artifact replicas sold on the internet as presents.

The second video work ‘In search of Mohamed: Jabal Al-Nour (mountain of light); walking in solitude’ has been made by extracting point-of-view shots from the Arabic TV series “Qamar Bani Hashim”. The video conveys another technique that’s been used to circumvent the prohibition of depiction by representing the subject through the camera. The video puts the viewer in the prophet’s view while walking in solitude throughout Jabal an-Nour (Mountain of the light) which houses the cave of Hira where he used to spend time meditating, and where it is believed that he received his first revelation.

Similar to the footprint sculpture, I imitated the walking stick in the video by melting wax and sculpting it by hand to make the sculptural work ‘In search of Mohamed: relics #1; walking stick’. Both sculptures were made as a result of direct pressure from my body to a soft material that’s been directly transformed later into bronze.

For the slide projection ‘In search of Mohamed: archive of opening credits’, I built a photographic archive of the word ‘Mohamed’ from a large collection of Egyptian films. While watching the opening credits of the films, I grabbed a film-still whenever an actor named Mohamed is displayed on the screen. The second names were erased from the images, leaving the single word Mohamed with the original film scene in the background, creating an ambiguous connection between the written word and the image. The images went through a combination of digital, and sometimes analog processes that obscured the original film stills and changed their materiality. The images were printed, then rephotographed using positive films. The mechanical reproduction capabilities of the camera have been utilized to copy existing materials, decontextualize and repurpose them to build a photographic archive of the name. The slides are displayed on a slide projector controlled by a motion controller that is programmed to activate the projector when a body moves in the space.

The installation also includes a set of CRT TVs displaying extracted scenes from Egyptian fiction films when an actor/actress says the name “Mohamed”. The sound Mohamed is called asynchronously while the rest of the dialogues are muted. Those videos act as an audio-visual representation of the name Mohamed from the films I used to watch back home on similar kinds of TVs.

The sound in the video ‘In search of Mohamed: following the invisible’ has been created by Sammy Sayed.

(1) Ali, Wijdan. From the Literal to the Spiritual. The Development of the Prophet Muhammad’s Portrayal from 13th Century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th Century Ottoman Art. In: Electronic Journal of Oriental Studies. IV (2001), No 7, pp. 1-24. Zie: www2.let.uu.nl/Solis/anpt/ ejos/pdf4/07Ali.pdf

(2) Perween Hasan, “The Footprint of the Prophet,” Muqarnas 10 (1993): 335–43, https://doi.org/10.2307/1523198.

Response to Ezz Monem’s work In Search of Mohamed

By: Leanne Bock

Ezz Monem’s immersive installation combines excavated, analogue, archival imagery from his homelands,

using projectors, slides and TVs to conflate a multiplicity of narratives and realities.

Drenched in darkness,

the artist invites us to his vantage point.

Encircled by, yet removed from, mediated scenes.

Drifting out of the darkness

we supernaturally levitate through a gaping rocky mouth.

Howling, crackling, buzzing sounds build in intensity,

as if a biblical plague of desert locusts, is imminent.

Eerie anticipation heightens, with invisible forces, deserted landscapes and buildings.

Doorways open and close with measured control.

An apparition stains the sky blood red.

The context of technicolour, telenovela style TV fictions

clash incongruously

with desaturated, grainy, documentary-style slides, overlaid with Arabic text.

Soldiers, blurred faces, gestures, streets,

mark the identity of people, place and phenomena,

framing layered historical references.

The indexical quality of found footage

evokes a single doorway

in the plurality of time and space.

The affect of memory intercepts,

as personal bleeds into the political.

Again, the blood-red filter.

A woman’s throaty whisper chants ‘Mohamed’.

The slide projector mechanically clicks in response, with measured control.

Projections onto plywood, an impenetrable doorway of sorts,

materially echo the dry, porous, north African landscape.

We’re embedded ecologically and culturally,

in a staged search, for Mohamed.

The Islamic prophet and messenger of Allah?

or Mohamed the artist, Ezz’s birth name, bearing the imprint of identity, experiences, perspectives, values,

beliefs, and continually seeking to reconcile these

as they morph over time on different lands…

Or,

are we searching collectively for a perspective, to configure a whole?

In Search of Mohamed traverses identity and place,

pivoting from the artist at the centre point.

With fragmentation and ambiguity,

it addresses overlapping themes of surveillance, power, authority, diversion, ideology and conflict.

An indeterminate exploration, discovering only that searching

is a continual state

of being.

‘In Search of Mohamed’, installation shots at the VCA Artspace, multi-channel video and sound, 35mm slides, Kodak Ektapro slide projectors, CRT TVs, plywood, 2021.